by Mark Stone

Clashing with cold, factual style of the original film, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2 decays into a putrid slice of horror-comedy pie, which never tasted better than it did in the 80s. It stands firmly next to other classics of the subgenre, with no better comparison than to 1985’s The Return of the Living Dead. Tobe Hooper was originally attached to The Return of the Living Dead as director, before being replaced by Dan O’Bannon. The following year, Hooper created The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2, channeling the spirit of that magical 2-4-5 Trioxin potion from The Return of the Living Dead. Chainsaw 2 has most of what folks love about Return: likable characters subjected to nightmarish scenarios, gorgeous practical effects and design, as well as copious amount of then-current rock and punk music.

You will rarely find characters like these, elsewhere. Our protagonists are “Stretch,” a radio dj with journalistic aspirations, and “Lefty,” a rogue Texas Ranger with a personal vendetta against our antagonists, “Leatherface,” “Chop Top,” and “Drayton Sawyer.” Caroline Williams plays Stretch as straightforward. Her biggest task as an actor, and it’s a big one, is reacting to the various horrors her character endures, including becoming the subject of Leatherface’s unrequited love. The real star is Blue Velvet-era Dennis Hopper as Lefty. He is magical. He’s the guy you want on your side in a chainsaw fight, and he steals every scene in which he appears. Bill Johnson’s Leatherface departs almost completely from Gunnar Hansen’s portayal in the first film, becoming one half of a comedy duo with our Hitchhiker equivalent Chop-Top, played by Bill Moseley. Both are fun to watch and have some fantastic scenes, varying in range from proto-Rob Zombie-esque terrorizers to browbeaten siblings of Drayton Sawyer, the family patriarch played by Jim Siedow. The entertaining dialogue and banter never stops with our antagonists. (“What was that anyway, the Rambo III soundtrack?”)

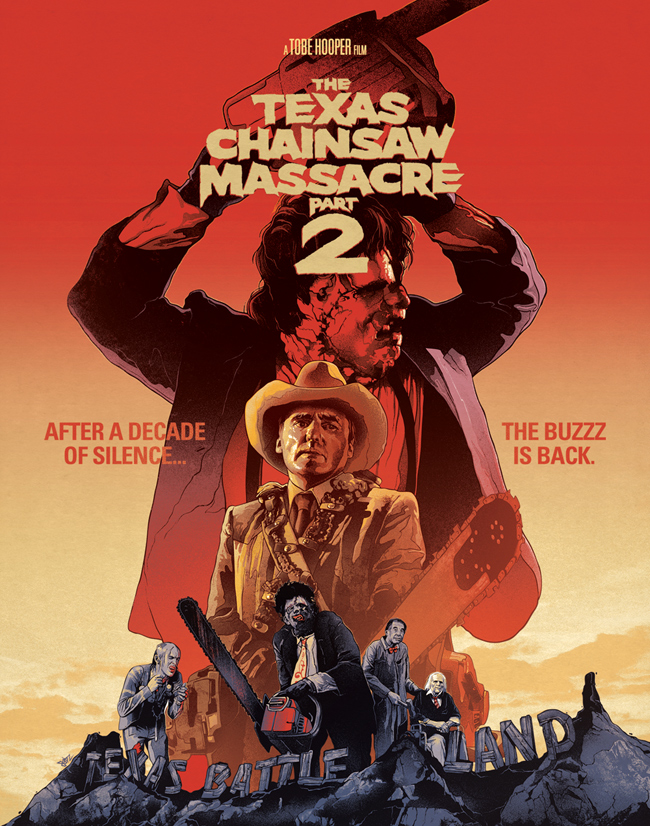

THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE PART 2, (clockwise from left): Ken Evert, Bill Johnson, Jim Siedow, Bill Moseley, 1986, (c)Cannon Films

From the radio station to the chainsaw shop to the Texas Battle Land bunker, I am constantly surveying the detail and creation going on behind and around the actors. The costumes and look of the characters are likewise pitch-perfect for this film. As with the backgrounds, I always find myself distracted by things like Chop-Tops button-pins. The real star, however, is another excellent display of practical effects by Tom Savini. Leatherface’s mask this time appears to be stitched together from at least four or five different faces, each with independent skin tone, hair color, facial hair, etc. There are skinned bodies, exposed metal cranial plates, sawed off heads, and, of course, the remains of the Hitchhiker from the first film, now lovingly carried around by Chop Top and referred to as “Nubbins.” It is a smorgasbord of pure foam, latex, and paint creation from its heyday. Yes, it’s the antithesis to the first film’s approach, but in the mid 80s, how could it have gone any other way?

Finally, oddly enough one of the most important elements to me, is the music. Jerry Lambert’s weirdly Bernard Herrmann-esque score fits the film as it’s a complete mockery of classic horror film scoring, something the original Chainsaw lacked. The successful Re-Animator was scored similarly the year before by Richard Band, evidence that Hooper was well aware of the horror-comedy climate. Hooper wisely chose to sprinkle the film with rock and punk songs, which to me fits the movie perfectly and elevates it. The Cramps’ “Goo Goo Muck,” and Stewart Copeland’s “Strange Things Happen,” are standouts, but none cement its personality like Oingo Boingo’s “No One Lives Forever.” This song, and the scene that accompanies it, announce to the world Chainsaw 2’s party-minded intentions. It screams, “Oh, you liked Return of the Living Dead? Well, how about THIS?”

Many folks deride this film as inferior to the first, and that’s completely valid. It isn’t as good as the first film. But it’s also apples to oranges, and I find it painful that many would guess Tobe Hooper simply whiffed its execution. The entire film can best be summed up by its poster, an overt parody of 1985’s The Breakfast Club. It is aware, it is funny, and it had purpose in a pre-Scream era.